In an earlier post, I talked about two types of knowledge:

- One type can be captured in systems, for example, manuals, guidelines and databases. It is objective, rational, and can be expressed in words and concepts. This is known as “explicit knowledge”.

- The other type cannot be fully captured in systems because it is in people, for example, intuition and discretion. It is subjective and experience based, and difficult to express in words and concepts. This is known as “tacit knowledge”.

Given their differences, I ended the last post by noting the importance for organizations to understand: (a) the nature of the knowledge that drives their missions and work, (b) how the knowledge is best created and shared, and hence (c) what knowledge management approach is best suited whether a systems approach or people approach or a combination.

Lest I have left people thinking that knowledge exists in either one form or another (e.g. explicit vs. tacit), there is more! Consider the following story:

In one of our classes, we learned how conflicts often emerge not because of disagreement in ideas but because of different communication styles. (This is a fascinating topic for another day!)

As part of our homework for this class, we had to prepare a presentation on our personal communication style and deliver it in the communication style of another classmate.

Let’s see what is going on in terms of knowledge:

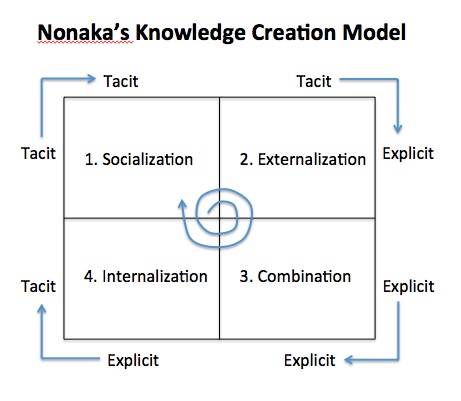

1. To do our assignment, we need to develop new awareness and knowledge about ourselves (i.e. unique to ourselves). We also need to reference what we have observed and experienced about our classmates. For example, I may notice that some of them are quiet and reserved, so I tailor my presentation to them. In doing so, I make assumptions about them (and likewise they make assumptions about me). Some of it may be false, but some of it will likely be true because we interact often and know another well. At this point, all the knowledge I have created is personal to me and it is tacit.

2. In creating and delivering the presentation, I convert some of the tacit knowledge into an explicit form. This includes the text, concepts and diagrams in my slides, and the words I use to present my ideas. Is the conversion from tacit to explicit knowledge 100%? Probably not, because I am not good with words and I may not explain my thoughts clearly. I am also given five minutes only, enough to convey some ideas but not all of them.

3. Following my presentation, I receive feedback from others. Some of them say, this part is spot on! Others say, that part is wrong (and why). Based on the feedback, I may revise my knowledge. Or, I may challenge and convince others, and they may revise their knowledge. As we do so, the knowledge that is out there in the open evolves. We may create new insights as a class (i.e. new knowledge).

4. Each of us will take away different things from the session (those who sleep in class take away nothing except maybe a more refreshed mind). As we internalize this, we convert the explicit knowledge back into tacit knowledge. Is the conversion 100%? Unlikely, because even though we go through the same experience, our interpretation and takeaways are different. Just as how we may attend the same meeting, but we draw different conclusions from it – sounds familiar? ;)

What I have just described is known as the Nonaka model of knowledge creation, and the numbers above correspond to the numbered steps in the diagram below.

Why is this significant?

- We can see that the issue is not whether knowledge is tacit or explicit, or which form is better. Rather, knowledge is both tacit and explicit, and there is arguably no better or worse form.

- We see that knowledge is “fluid”, switching forms as it is created and shared.

- Without this “fluidity” it becomes difficult to create and share knowledge effectively.

- The effectiveness of knowledge creation and sharing depends on all four processes (#1, #2, #3, #4).

Some people may argue that this is just one version of knowledge creation. For example, in their organization people do not come together to discuss issues and create knowledge. Instead, they wait for the boss to issue new instructions.

This is not uncommon. It may exist in some top-down or command systems. In such systems, creating knowledge tends to be seen as the responsibility of the boss (after all, he is smarter and is paid more right?). So, people may keep doing things the way they have always done (until they are told to change it). Even if they notice the old ways of working are no longer relevant, they may not think about trying something different, nor do they see it as their role to do so. On the other hand, the boss may sit in his room and create the new knowledge based on his perception of things (step #1), and convert that into a new directive (step #2). He issues the directive, which others internalize and apply (step #4). Step #3 may be weak or lacking, and effectiveness of the organization depends on the capability of the boss in correctly identifying and creating the new knowledge.

Now, compare this to another organization where knowledge creation is seen as the responsibility of more people (or everyone). Such systems can feel chaotic, especially when everyone makes their tacit knowledge more explicit, and engage in protracted debate.

Perhaps this is what scares bosses – the need to spend time and effort to make sense of many streams of knowledge. At the same time, if we can manage the process in an orderly way, so that the knowledge is subject to scrutiny and discussion, there are many ways the knowledge can be combined to create new knowledge.

This brings us to another point – the importance of the externalization (#2) and combination (#3) steps in knowledge creation. Whether at the individual, team or organization level, the more we make our knowledge explicit and allow it to interact and combine with the knowledge of other people, teams or organizations, the more likely we create new and better knowledge. This is the rationale behind brainstorming, where in the early stages the focus is often on the quantity rather than quality of ideas – in fact no idea is ever too silly! This is because the more (and diverse) ideas mixing together, the better chance of creating something useful.

However, it also means we must be prepared to allow our knowledge to switch in its form, and combine with other knowledge. If we hold our cards close to ourselves and refuse to share our thoughts with others, or if we refuse to consider the ideas of others, we can do lots of brainstorming but essentially remain fixated in our minds. We would fail to create knowledge.

However, it also means we must be prepared to allow our knowledge to switch in its form, and combine with other knowledge. If we hold our cards close to ourselves and refuse to share our thoughts with others, or if we refuse to consider the ideas of others, we can do lots of brainstorming but essentially remain fixated in our minds. We would fail to create knowledge.

In conclusion, building on the last post, we can be in a better position to apply knowledge management in organizations when:

- We appreciate the dynamic nature of knowledge, how it can switch from tacit to explicit form, and vice versa.

- We are conscious how the switching of knowledge between forms can facilitate the creation of new forms of knowledge

- And we support this rather than resist it.

Now that we know this, how does knowledge creation and sharing occur in your organization, and how do you think it could be enhanced?

photo credit:

Rangga Chandra via photopin cc

Stanley – I LOVED how you incorporated communication styles into your post. By using how we communicate as an example for Nonoka’s Creation Model of knowledge you hit home an even more important point (maybe without realizing it?). To me, this seemed to highlight the vital importance of recognizing emotional intelligence as a key form of knowledge in organizations. I feel as though the label “knowledge management” immediately invokes the management and organization of traditional knowledge systems (SOPs, processes, numbers, etc.) rather than the importance of understanding and managing emotional intelligence as well. Tacit and explicit modes of emotional intelligence are in many ways extremely more difficult to share and absorb across organizations and need to be recognized by leaders as key components of organizational success.

@Andee – What a great insight! Thanks for raising this, because I did not notice the role of emotional intelligence in this, but now that you mention indeed it is important and difficult.

This “combination” might not have emerged if I had not externalized my thoughts where you could comment on it. Ah, Nonaka would have been happy to see a discussion on his knowledge creation model being an illustration of itself :)